WARNING: WORK IN PROGRESS. This text is a huge mess, but if I wait for the moment where I have enough time to polish it up, it will all be obsolete or I will simply be dead. Therefore I dump it on the internet as-is and will update it whenever I see fit, which could be: tomorrow, next month, in ten years, or never. Consider yourself warned: do not expect a coherent whole despite the fact that the first sections may appear well-structured.

This text is the successor to my older rant, which to be honest is crap for a large part. It is still available though for the interested.

TL;DR: this is not a text for people who think everything can be summarised into a single sentence.

Last (significant) change: 2024/11/14.

A short note for Dutch-speaking readers / Een opmerking voor Nederlandstalige lezers

Er was een Nederlandstalige versie van de oude editie van deze tekst, maar aangezien ik nog niet eens de tijd heb om deze Engelse versie deftig af te werken, heb ik zeker geen tijd om een vertaling te maken. U kan proberen het door een automatische vertaler te draaien, maar hou er rekening mee dat dat niet altijd betrouwbaar is. Ik raad u sowieso aan om Engels te leren en indien mogelijk nog een paar andere niet-Germaanse talen, er zal een hele wereld voor u open gaan.

Before you start reading, a few rules

- You must not read this text if you are younger than 16 years, are in a depression, belong to an extremist religion, or have never thought with at least some depth about the meaning of life. If you are a fervent humanist who believes humanity is infallible and who cannot stand any criticism about it and rather sticks one's head in the sand than listening to arguments why we should do certain things differently, then this text is not for you. Most likely you do not want to read this text at all but of course you will only notice that when it is too late. The author of this text cannot be held responsible in any way for possible malicious consequences of the reading if this text. It is solely at your own risk.

- You must not force anyone to read this text (obviously especially not anyone from the groups mentioned above). You may suggest it, but must respect their decision if they do not want to read it.

- You must not read this text if you do not want to, even if anyone else asks or urges you to.

- You should not link to this page or put it on a social network site unless you really, really want to. I have not put any visible links to this text on my site or elsewhere, with the intention that people will only find it through search engines. I would like to keep it that way. If you do want to link, you must link to the top of this page, in other words make sure these warnings are not skipped.

- If you are adamant about posting a part from this text somewhere but you want to honour the previous rule, feel free to either copy that part or rewrite it in your own words. The main reason why I do not want to brag about having written this text by pasting my name all over it, is because a lot of it is merely a reformulation of things that others figured out long ago. And I am too busy (or lazy) to research whether those parts I did figure out by myself, have not already been derived before. The whole idea of this text is that it does not matter who wrote down something, it is the content itself that matters. It would be nice if you would stay true to this idea by not making it seem as if anything you copy from this text is your own work. If anyone asks for the source, try to get away with: “I found it on the internet.” If they keep asking, of course I will not mind if you do give them the link.

- This text is not a scientific publication that has gone through a rigorous review process (then again, as the text itself explains, even that would not guarantee anything). It is a big smorgasbord of logical thinking, opinions, and some emotions. Do not blindly accept anything you find in here, be critical.

- You must not do anything stupid inspired by anything in this text. Really, don't. If you do anyway, I distance myself entirely from it.

- This text contains expletives. If you do not want to read a text containing expletives, then in all likelihood you wouldn't want to read this text either with the expletives removed.

- Usual copyright stuff applies to this text, even though I deliberately omitted my name. You must not copy parts of it in publications without my permission. That would violate the second rule anyway. If you are a student and believe to be smart by plagiarising this text, be warned that I have already noticed that this page is often fetched by automatic plagiarism detectors.

- You shall not mail me about this text nor shall you speak about it if you ever meet me in real life, unless you are certain you have a very good reason. Some examples of bad reasons are: asking clarification about anything that you could also look up yourself, or throwing an emotional tirade at my head because you feel insulted about something. And please no mails in the vein of:

I agree with your text, but may I suggest adopting [insert some common way-of-life here],

that basically mean as much as:I did not read or understand your text at all,

or:I want to shove my way of life up your nose,

or:I have no control over the instinctive part of my brain that still lives in a small village where it was efficient for everyone to be similar.

I am also not interested if others wrote texts similar to this one, I know that is obvious. I did not write this to elicit a discussion with others, I do not like to participate in lengthy discussions. I did it mostly to vent off steam about stuff that bothers me in everyday life. I do not want to be reminded of that stuff. This text is basically a few hundred pages of bile distilled into text, glued together with reason in an attempt to reduce or even neutralise the bitterness of the bile. Many of the conclusions in this text came at the time when I was working on it. This could be considered a kind of polished ‘brain dump’. - Even if you just want to say “thanks” because you feel this text changed your life or something, I'd rather you would not. If you agree with the text, then do something in your life that will visibly improve the state of the world so I can see it happening. That will put a much bigger smile on my face than a textual message that probably only boils down to:

I agree but I am too lazy / chicken / scared to act.

The core idea of this text is something that cannot be grasped in language. Either the reader will already know what I am trying to tell here or not, but they will not get the point by reading this text unless already on the verge of figuring it out by themselves anyway. That makes this whole heap of text mostly useless except for some generally applicable concepts you might learn from it. Again, I mostly wrote this to order my own thoughts as a kind of therapy.

I repeat: you will most likely not want to read this text anyway, because it will either attack your entire way of life, or explain things you already know or were about to find out anyway. This is not the kind of feel-good text full of politically correct ideas made up by people who believe that bad things can be made to go away by consistently ignoring them. This text lifts up all your carpets and shows how much dirt you have wiped under them in the hopes of never having to clean it up. It is like a party pooper who replies to all questions of other partygoers with dry logical answers that spoil all the fun. Reading it might produce for some the same sensation as taking a brick and bashing it into their own face. Continuing to read it all the way through the end, may feel like picking up that brick again and bashing it in their face over and over again. Do not tell me I did not warn you.

Hint for the adventurous readers

If you see anything like “[LINK:TOPIC]” in the text, it means there must somewhere be a section marked with “[REF:TOPIC]” that the link should point to. I intend to replace this with actual hyperlinks when the text would ever reach any degree of maturity. Until then, you will need to use the ‘find’ functionality of whatever device you are using to read this page. This will probably cause you to jump around uncontrollably in the text, but that will not matter because it has a serious lack of structure anyway. If you see an asterisk (*) between paragraphs, it often indicates a complete change in subject without titles or introductions.

Why Do We Live? What Is the Purpose of Life?

Possible subtitles: “A Text Nobody Wants to Read,” or “Sorry, the Handbrake on My Brain Is Broken.”

Why do we live? This is a question that most people will ask themselves at some point in their lives. And many of them will fail to find a concluding answer. That is not so surprising given the answer itself. It is in fact so simple that most do not even consider it a possible answer. I am not claiming here that I am absolutely certain of knowing the real answer but I believe I am pretty close.

Now, the major problem is that it is rather pointless to give the answer. According to the ‘Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy’, the meaning of life, the universe and everything

is ‘42’. That does not make sense but it is likely that to many readers of this page, neither will the real answer. As will be explained below, really understanding a specific concept is only possible for someone who either has the right context or comes close enough. In other words, either you already know what this text is about or you were about to realise it yourself anyway; in all other cases you will most likely not comprehend what I am going to say. So this whole text is actually useless. You'd better stop reading, I mean it. I have only written it as a kind of self-therapy to vent off steam. If you decide to read on anyway, well, it is your own time you're wasting.

To the Point

I will not take any roundabouts and just summarise The True Meaning of Life™ in the next paragraph. The entire rest of this text is just an illustration of what this means, why other explanations are less likely to be correct, and what consequences it has for the things people do every day.

Here goes: there is no goal to life, at least not any goal that clearly dictates a certain optimal way of life. We live because billions of years ago, by a conjunction of circumstances, life has originated on Earth. Life is nothing more than a combination of chemical and physical processes that are able to maintain themselves thanks to addition of energy, the most important of which is solar radiation. This life has mutated and the mutations that were unfit for continued existence have died out. The others have mutated in their turn, and this process has repeated itself countless times. This has led to what we are now. In short, we only live because it is possible for us to live. If we jeopardise this possibility to live, we jeopardise our own existence.

So, there you have it. The above paragraph is clear and unambiguous, and everyone who can read English should understand it. Yet, there is a vast difference between understanding what I am trying to tell, and fully realising what it means. The difference between both is the same as between one the one hand just assuming that a certain mathematical proof is correct because you know some smart person has proven it, and on the other hand making the proof yourself and understanding every single step of it, as well as every single step in every other proof that this particular proof uses to prove its own statement. Mind that I do not claim here that I can prove what I have written above, or every intermediate step to reach that conclusion. I can however fill quite a few of the gaps in the reasoning that leads to the above conclusion, instead of just assuming that it is correct. I believe the resulting explanation, despite the fact that it is still uncertain, is a lot more plausible than the various things many other people blindly believe in.

Some things I learnt from the previous iteration of this text

An older version of this webpage was written in a way that made it seem as if I was the only person who realised the above. This was because I wrote that version only shortly after coming to that insight myself. The next section will explain why this gave me an illusion of knowing more than most other people. Other sections of this text will explain why this made me arrogant [LINK:ARROGANCE]. In the meantime I have realised that all those things I figured out through logical thinking, and which I painstakingly wrote down over the course of many years, have already been written down by others, probably long ago. My goal for this new iteration of the text has therefore merely become the bundling of all that long-known but sometimes mothballed knowledge into one lump of text. And especially, to write that text in plain language with as little jargon as possible, and keep it structured such that anyone with a basic level of education could pick it up from the start, and not be bogged down by implicitly assumed prior knowledge. I did not stuff the text with mathematical equations to express things I could also say in words. Some have mailed me about the old text, stating that it was a revelation, others said it only confirmed their thoughts, and others claimed it told nothing new and they were certain the majority of people understands its message. And of course there were also some predictable mails from persons who attacked certain parts of the text in an attempt to funnel their raging emotions.

Even though it is obvious to me now that there is a substantial number of people for whom this text cannot bring anything new, I am certain it is wrong to assume that most know it. Maybe those who mailed me, only really meant: “most people I know,” because on a very, very regular basis I encounter people who act in ways that demonstrate that they obviously have no clue about the core message of this text. Let me remind you: I do not want to receive mails about this text. I do not want to be reminded of it. I do not even want to know if this text changed your life for the better or something. That is the very reason why I tucked this lump of prose away in a corner of my site without any visible links to it. I should not have put this online at all, but part of me could not resist doing it anyway. If you do want to show your appreciation, then live like it so I can see the world change for the better.

The main problem with the realisation above, is that at first sight it is utterly useless. It is generally very difficult to tell from someone's behaviour whether they act according to that idea, let alone whether they are aware of it at all. In most everyday situations, its knowledge will not influence decisions. Only for specific core decisions with far-reaching consequences, it can make a huge difference. For anyone who has only recently fully grasped the gravity of the realisation, it may be tempting to feel superior if it appears they are the only one with the insight. This was the case with my very self when I wrote the old text long ago. It is also tempting to keep on ignoring all the evidence that a considerable part of the rest of the world has already gone through this phase long ago and moved on towards a life where on a superficial level they appear to be unaware of this realisation. Admitting to that, would mean letting go of yet another ego-booster [LINK:ARROGANCE]. This scenario does not only apply to this True Meaning of Life™ idea, but also to more mundane things, but don't worry: in the rest of this text I will most likely bore you to death with numerous other references to people locking up themselves into a small frame-of-reference in order to protect themselves from the risk of feeling insecure.

An interesting fact: the previous version of this webpage existed in both an English and Dutch version. During the years that the previous versions had been online, I kept statistics of the visitors. Even though the number of Dutch-speaking people globally is negligible compared to English-speaking people, the Dutch page had accumulated three times the number of visitors over the same period. Moreover, within this Dutch-speaking group of visitors, the Belgian ones accounted for more than twice the number of visitors from the Netherlands, despite the fact that the Dutch-speaking Belgian population is far smaller than the population of the Netherlands. I am not sure what kind of conclusion to draw from this, but it seems to indicate that the willingness to philosophise about life is strongly geographically dependent. This is not surprising as such, but the discrepancy between the tiny Dutch-speaking community and the massive English-speaking community is striking.

I wrote this text directly in English. I will probably never translate it to Dutch because of the insane amount of work it will require. The fact that I did not write this text in my mother tongue proved interesting later on, when I discovered a certain scientific article: [KeEA2012]. Apparently it is much easier to reason logically in a foreign language. It was also often exactly while I was writing things down here, that I figured out new conclusions.

What to expect

I will start out in the next section by explaining why reading this text is mostly pointless if you did not yet come close to understanding its core message yourself (in which case it obviously is also pretty pointless).

By the way, if you wonder why there are only very scarce references in this text in the sense of citations of scientific articles, it is because I have not directly read any scientific articles about most of what I am talking about here. Most of it is deduced from basic facts that I explored elsewhere in this same text. Some of it is inspired by things I remember from too long ago to find back the actual reference. This text is not intended to be rigorously scientific, it is more of a bird's-eye view on reality. The main idea is that it should stand on its own. As will be discussed further on, I am starting to have my doubts about the current trend of science being treated as a huge dumb database of piled-up keyhole-view observations with little to no attempt to find relations between them or search for the root cause behind the observations.

I believe that once a scientific study based on measurements (as most studies are) leads to a logical conclusion that stands on its own, then there is little use in keeping to refer to the measurements themselves (although they should always be kept and occasionally re-verified). Moreover, I believe that if a fact can be proven through a watertight string of reasoning, then an experimental validation of this fact is not only redundant but also risks making the proven fact appear invalid through observer bias or overseen (maybe intentional) errors in the validation procedure.

If you want to verify anything yourself, go ahead and do some research. Do not readily believe what is written here or anywhere else. It can be wrong and some things are in all likelihood wrong. Who knows, maybe I intentionally added some wrong stuff here and there to test anyone who reads this. Or maybe I did not. You must learn to think for yourself. Do not be an ape that only copies things.

If you are the kind of person who approaches reality like a mathematical proof, stubbornly rejecting everything that has not been proven with 100% certainty, believing that at some point you shall be able to grasp the entire complexity of the universe without admitting there are things you will never understand or resorting to approximations like statistical models, then you might as well stop reading here: this text is not for you. Its purpose is not so much to give readymade answers as it is to raise questions and take a wrecking ball to all the assumptions that humanity has been collecting since its inception—and even way before that. Again, if you are the kind of person who does not even allow raising questions over things assumed to be proven, this text is not for you. Or maybe it is after all…

Perceptual Aliasing and Learning

The true enemy of knowledge is not ignorance, it is the illusion of knowledge.

— Stephen Hawking

There is a fundamental problem when it comes to explaining people—or any intelligent being for that matter—any concept that requires even the slightest bit of background knowledge. Which is, pretty much everything. It can be the core message of this text, it can be the reason why someone is wrong about something, something artistic, something technical like for instance why a modern stick shift petrol car will consume more energy if you bring it to a halt by pushing the clutch and then braking than if you only depress the clutch pedal when the engine is about to stall, and so on.

The phenomenon is simple, obvious, and has been known for ages. Yet few seem to be truly aware of it. There is not even a general name for it as far as I know, or maybe I missed it. Just to be able to refer to it further on, I call the problem ‘perceptual aliasing’. The phenomenon is obviously long known in literature. As I figured out only very recently, it is closely related to the Dunning-Kruger effect [LINK:HUBRIS]. What I want to explain is more general though and I will therefore refer to it using the ‘aliasing’ term, for reasons I will soon explain.

In this text I define perceptual aliasing as: “the phenomenon where the larger an observer's inability to comprehend a certain subject, the more unaware this observer becomes of its own inability to make correct judgments about this subject.” This may sound blatantly obvious because in a certain sense, it is. Yet it is easy to overlook the important nuance in this definition. It does not merely state that increasing lack of ability to comprehend something increases the lack of understanding—that is plain obvious. Instead it states that at a certain point, the observer will not even be able anymore to understand why it is unable to make correct judgments. It has a risk of misperceiving its inability as an ability. There is some regularity in how the judgment is distorted. In general, a certain relation exists between the degree of incompetence and the perception of understanding, and this relation has some surprising consequences.

Aliasing

Suppose two persons, A and B, have vastly differing intellectual capacities with A being the most intelligent. If A tries to explain something which is far above B's level, B will not just be unable to understand the explanation. The key problem that lies at the base of perceptual aliasing is that B is also likely to be unable to realise his inability. The farther B's upper limit is removed from the required level to understand the matter at hand, the larger this likelihood becomes. It is possible that B ends up thinking A is dumber than him and is telling nonsense, or even that he thinks he does understand the explanation even though he does not.

The term ‘aliasing’ means that B's judgement about the correctness of A's explanation will be an incorrect projection of the right judgement inside B's limited frame-of-reference. The judgment that B finally relies on will be some alias of the true correct observation, but B will be unable to be aware of this. When observing either the alias or the actual observation, B sees no difference.

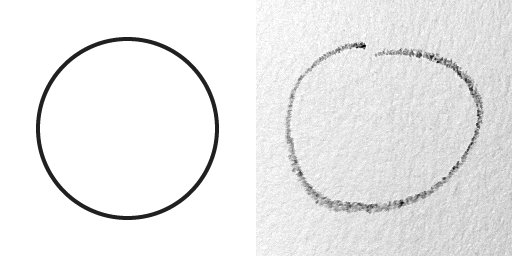

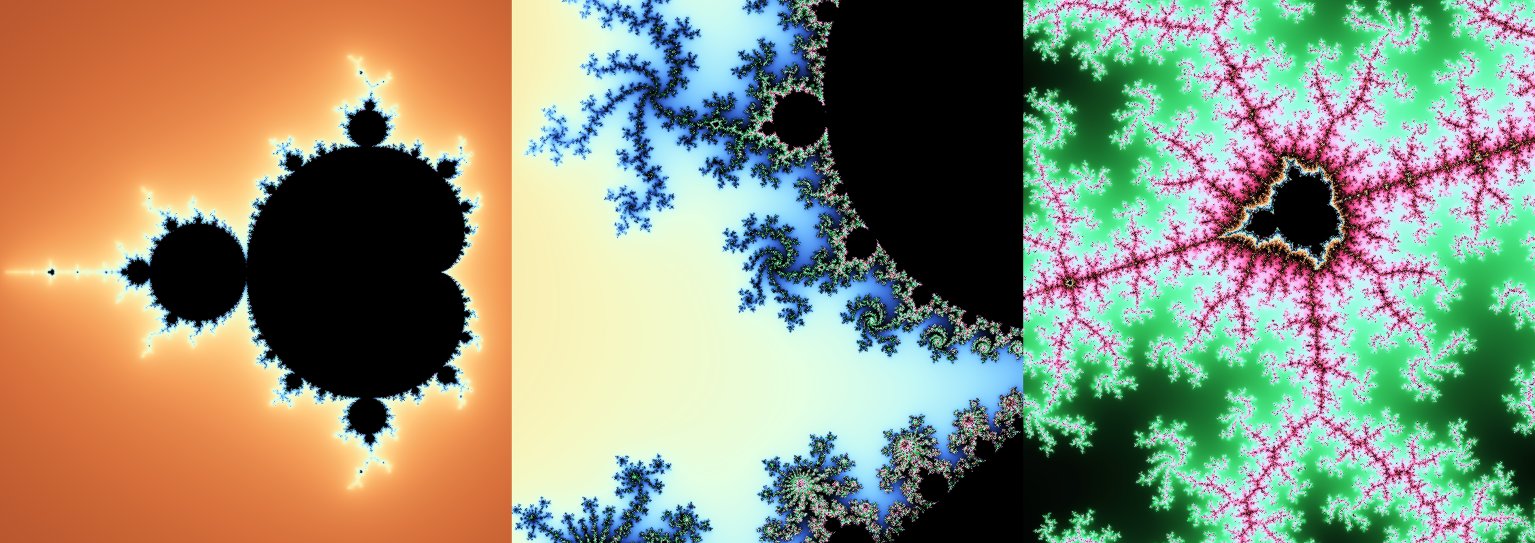

This may all seem a bit abstract, so I shall explain the physical phenomenon from which I borrowed the term aliasing. The concept comes from the field of signal theory, and is important whenever one wants to represent a continuous signal like a sound wave or a moving image with a limited number of data points, so-called ‘samples,’ or ‘frames’ in case of a video. Aliasing can be easily understood, and is best known from the phenomenon in video recordings where spinning wheels appear to start rotating backwards as they spin forward faster and faster. This starts happening when the wheel makes more than half a turn in between two video frames, in other words when the number of revolutions per second is more than half the video frame-rate. Within the ‘universe’ of classic cinema where the frame-rate is 24 frames-per-second, wheels that spin faster than 12 rotations per second cannot exist. They are all aliased to wheels spinning at apparent speeds between zero and twelve rotations per second in either direction. There is no way of knowing if a wheel that appears to spin backward is not actually spinning forward fast. Heck, even a wheel that appears not to be moving at all could be spinning at any multiple of 24 rotations per second.

This has been formalised in the Nyquist-Shannon sampling theorem: if a signal is sampled at a certain rate, any frequencies higher than half this rate (the Nyquist frequency FN) cannot be represented, and will ‘fold back’. The frequency of their sampled counterpart will be below FN, by the same amount as the actual signal is above FN. The seemingly lower frequencies in the sampled signal are said to be ‘aliased.’ They are incorrect projections of the real thing, but there is regularity in where the projections end up. A signal of twice FN will appear as a frequency of zero, and from that point on the aliased frequency will rise again. It constantly bounces back and forth between zero and FN (strictly spoken, between -FN and +FN).

The Nyquist frequency for classic cinema is 12 Hz. A wheel spinning at 16 cycles per second will appear to spin at 8 cycles per second in the other direction. A wheel spinning at 24 cycles will appear to be stationary, and at 25 cycles it will seem to spin at 1 cycle per second. The above figure illustrates this for the case where the frame rate is initially eight frames per revolution of the wheel. The subsequent rows show what frames are obtained when either keeping the frame rate constant while speeding up the wheel by an integer factor, or keeping the rotation of the wheel constant while reducing the frame rate.

Wheels that have a radially symmetric structure, for instance if they are constructed with spokes, will exhibit aliasing in classic film at much lower speeds than 12 revolutions per second, because for a pattern that repeats say two times, the wheel will appear identical each half revolution. The Nyquist frequency for such wheels is divided by the number of times the pattern overlaps with itself across one revolution. For instance, around 32 minutes into the film ‘Once Upon a Time in the West,’ there is a nice example of aliasing to be seen on carriage wheels that appear to turn backwards, because those wheels have 16 spokes and will therefore exhibit aliasing when they make a complete turn in 1.33 seconds or less. The only way a spectator could readily see that a wheel is spinning faster than can be represented by the frame rate, is if the exposure time per frame is long enough that motion blur becomes obviously visible. The aforementioned scene however was shot in bright sunlight hence required a fast shutter speed which resulted in frames with nearly no blur.

Recognising Intelligence Requires Intelligence

Why the above diversion about signal theory? Well, I believe a similar phenomenon applies to humans when they judge a situation, problem, or subject. Of course, those things do not involve anything like sampling a signal at regular time intervals, even though arguably they are still based on a limited discrete ‘sampling’ of a continuous truth. Intelligence is one example but it also applies to other subjects like a certain field in science or the appreciation of a certain art form; anything that requires knowledge, a context or frame-of-reference, to be understood or appreciated. The ‘frequency’ would then correspond to an intelligence level, knowledge about works of art of that kind, etc. Someone's ‘sampling frequency’ would correspond to that person's own level or capabilities. The main reason why I find the term ‘aliasing’ appropriate, is that it refers to multiple different realities being mapped to one single observation that may or may not be the correct one, which is exactly what happens in this human context.

The root cause of perceptual aliasing is that humans lack a robust mechanism to detect their inability to understand concepts. Instead, they tend to be overconfident and desperately yet unconsciously try to re-map anything they do not understand to something they do know. One can see why this can make it useless or even risky to explain someone's mistakes. If that person is vastly unable to understand the cause of the mistakes, they may think the other person is telling nonsense or worse, is insane. To put it bluntly, it is pointless to explain to an idiot why they are an idiot, because only those who have already raised themselves far above the level of idiocy can understand why someone is an idiot.

Luckily the parallel between perceptual aliasing and the sampling theorem is not to be taken too strictly or it would imply that learning is impossible. It is hard if not impossible to map for instance an intelligence level to a single number like a frequency (although some believe they can, for instance with IQ scores). Most of all however, while aliasing in the frequency domain is strict, in the case of human perception there is a certain ‘fuzziness’ at the edges. Someone who is only slightly below the level of another person can actually learn from this and boost their own level. This is why the best way to learn for instance a game like chess is to play against opponents who are slightly better than you. You will not learn from someone who does nothing that you do not know yet, but on the other hand the moves of an opponent whose level is way beyond yours will just seem random to you and you will not learn either, or learn the wrong things. Of course you can learn from someone with a much higher level, if that person can gauge your level and restrict themselves to play the game at a level only slightly higher. This is a skill on its own and is what sets a successful teacher apart from a mere professional. This is why it makes sense to speak of a ‘learning curve’: one can only learn something properly by following a smoothly rising curve, not by trying to take sudden huge leaps.

As with the sampling theorem (think of the spinning wheels), it is possible to ‘fold back’ between zero and the maximum frequency indefinitely. It is perfectly possible that someone thinks they understand something while they do not, because their perception may have folded back exactly to a point of apparent understanding. In other words, people will in many situations be unable to realise that they do not understand something. This is more or less what the Stephen Hawking quote at the start of this chapter is saying.

Let's go back to our persons A and B from the first paragraphs. Remember, A is significantly more intelligent than B. Suppose they face a complex problem. B might come up with a solution that seems perfect because he does not see any obstacles. However, A may detect hidden flaws in this solution that will cause more problems later on, or subparts with an unacceptably high probability of failing. However, person B ignores those obstacles because he cannot even understand they exist. A's explanation may seem like nonsense or may fold back in B's perception to something that appears solvable after all. If B is lucky while executing his solution, the highly risky action(s) may work by chance, and the hidden flaws may not be immediately apparent. Because person A had concluded there was no acceptable solution, person B may then appear more suited for the task of problem solving and be assigned to solve other problems in the future, with disastrous consequences. I believe this scenario occurs often in reality. Generally, if someone is very enthusiastic about something but cannot tell what its weak points are or why exactly it is so great, be very wary. Some however are pretty good at instantly making up a bullshit explanation and make it seem plausible at the same time, therefore always be wary.

IQ

Even for those who get lost in all the signal theory behind this explanation, there is a clear-cut conclusion to be remembered from of all this. It is fundamentally wrong to assume that someone shall be able to reconstruct the entire string of low-level reasoning that has led to a high-level concept, by giving this person only that high-level conclusion. They may appear to be able to, and they will often believe they understand, but what they derive has a high risk of being wrong or incomplete. Their understanding of the high-level concept itself will be flawed in those cases. There may be a few who happen to have the right background to fill the gaps or have a higher capability of ‘connecting the ends’, but that does not mean everyone has that same background or capability. Yet, letting people derive a higher-level conclusion by themselves is a much better learning method than simply spoon-feeding the entire string of reasoning to them. Therefore the right way to do it is by giving them the right number of intermediate steps and letting them connect the dots themselves, while constantly monitoring them to ensure they are not going astray.

Likewise, testing someone's knowledge about a topic by only asking very advanced questions, does not guarantee that someone who gives the right answers really has a correct understanding of the entire topic. This person might just have studied all the advanced details about unusual situations by heart, while lacking the ability to correctly operate at the everyday lower level.

While using the ‘aliasing’ analog, I only considered one-dimensional signals that can be represented by a single frequency (e.g., the rotational speed of the wheel in my cinema example). This is of course another major difference with human thinking: the ‘signal’ at hand is not one-dimensional, nor two- or three-dimensional, but of a staggeringly high dimensionality. The limited sampling interval then becomes a ‘box’ or hyper-rectangle in this multi-dimensional space.

Coming back to the idea of an IQ test, what I wonder is how an entity with a given intelligence level could construct a test that could accurately measure beyond that entity's own intelligence level. It would require insights in problems that are far beyond that level. If the person constructing the test had those insights, it would lead to the contradictory conclusion that their level would be higher than it is. An IQ test would not be able to measure beyond the level of the most intelligent person who constructs it. It is possible that the problems constructed in the test can be solved in a smarter manner than the composer of the test intended, giving different and therefore apparently incorrect results. One might be tempted to rely on tests that one cannot solve oneself, and consider the ability of someone else to solve those problems a proof of higher intelligence. Of course this strategy is extremely flaky: the proposed solution may be wrong and neither the constructor of the test nor the purported more intelligent solver might be able to detect this flaw. In other words, such tests risk being subject to aliasing as much as the reasoning of real persons. Therefore I have very little confidence in any formal test that tries to measure intelligence, and I also wonder what is the whole point of it aside from ego-tripping. Quoting Stephen Hawking again: people who boast about their I.Q. are losers.

All the IQ tests I have seen, consist exclusively of a set of extremely synthetic problems constrained each to some single narrow problem space that has no link to real-world situations. It is not because someone is able to figure out what arcane number juggling was used to generate a set of numbers in a grid where one number was omitted, that they will be able to solve a real-world problem that involves combining observations from multiple senses and diverse knowledge gathered over many years.

Magic, Craziness, and Mathematics

For a general example of perceptual aliasing, consider the concept of magic, as for instance associated with witchcraft and sorcery. Suppose I am a modern female doctor and I am able to travel back in time. I teleport myself to a village in the Middle Ages, carrying current medications with me. I shall in no time end up being burned at the stake as a witch, because people from that time period do not have any background to understand state-of-the-art medicine, instead their background is built mostly upon superstition and folklore. It would take way too long to teach them about how the medication actually works. They'd rather kill me instead of going through that steep learning curve. A similar story holds if I would be a male scientist carrying current technology like lasers. I would be judged as being a sorcerer, because the people from that time period have no clue at all about electricity let alone quantum physics. Or as Arthur C. Clarke worded it: any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

On the other hand, consider the concept of ‘craziness’. Whenever someone exhibits behaviour that is not understood by others, there is always a strong tendency to instantly label that behaviour as ‘crazy’ or ‘insane’. This concept seems similar to magic, only it is just subtly different as I will explain below. The concept of ‘crazy’ is actually much more dangerous than ‘magical’.

The built-in instincts for the very concepts of both ‘magical’ and ‘crazy’ seem to have evolved for the sole purpose of allowing humans to somewhat cope with things they do not understand. In a certain sense they are similar to the concept of imaginary numbers in mathematics. The imaginary unit i (or j for engineers) is defined as the square root of −1, in other words i multiplied by itself equals −1. The definition of the square root s of a number x is that s multiplied by itself produces x, or s2 = x. This has as a consequence that for any real number s, its square x can only be positive because multiplying two negative numbers always yields a positive number. Therefore when students are first being taught the concept of square roots, the teacher will most often stress that it is impossible to take the square root of negative numbers. That is true only if one remains limited to the use of real numbers. By treating i as something special, something imaginary outside the field of real numbers, taking the square root of negative numbers suddenly becomes possible. The square root of any negative number s then becomes i times the square root of −s.

Although it is possible to understand what the square root of a negative number actually means, it often is unnecessary, hence even when students are later on introduced to imaginary numbers, usually these keep on being treated as something magical. The mere definition of imaginary numbers allows people to use them in quite a lot of computations without requiring the deeper knowledge. Only for more advanced operations where the imaginary numbers cannot be factored out, it becomes necessary to delve deeper. Much deeper in fact, the step between making abstraction of the incomprehensible and actually comprehending it is often staggeringly steep. Magic is actually a very good analog for the imaginary number i, craziness not so much. The difference between both is that there really is no such thing as magic while insanity does exist. This implies that the act of mapping incomprehensible things to magic is actually much safer than mapping them to insanity, because in the latter case there is a large risk of throwing away perfectly correct information just because of an inability to understand it. It is better to file that information under a label ‘magic’ and define this label as: “to be investigated when more capable and the need arises.” Calling something or someone ‘insane’ on the other hand is a cheap and quick way of giving up on trying to understand it, and taking a hostile stance instead.

Zero Point: Floating Reasoning

[TODO: NOTE TO SELF: I think this part sounds like Chinese 中文 to someone who is not familiar with signal processing, TODO: try to clarify with figures.] Another difference between perceptual aliasing and signal aliasing concerns the ‘zero point’, i.e. a frequency of zero, the bias or so-called ‘DC’ value. DC stands for ‘direct current,’ which would correspond to the average current flow if the signal being analysed is a variable electrical current. In classic signal theory, the zero point is always present regardless of the sampling frequency. It represents the overall average signal value. Not knowing this value means it becomes impossible to reliably compare signals because regardless of how good the knowledge about higher frequencies is, not knowing the bias means the absolute signal value is unknown.

Even a sampling frequency of zero (one single sample) could reliably represent the bias value depending on how it was obtained. In human thinking however, the ‘zero point’ may be higher than zero. In this sense, it may be more appropriate to compare human thinking with polyphase sampling or modulation, but the parallel with regular sampling on its own is dodgy enough already that I will not even try to go beyond it. What I mean with this variable zero point, is that the level at which people can manipulate concepts in their minds does not only have an upper limit, but also a lower limit that does not necessarily need to be zero.

The fact that the mere concept of ‘zero’ was mostly unknown throughout a large part of human history, including advanced civilisations like the Roman empire, is one telling example of this. I believe that even today there is a considerable number of people who do not have a complete understanding of the concept of zero. Those will also have problems with negative numbers: understanding them correctly requires correct knowledge about the true concept of zero. The greatest example however may be the very core idea of this whole text: realising that life does not really have a point, requires being able to go all the way to zero. Grasping the concept of zero and negative numbers, is akin to using the apparently depressing fact of the zero point of life to derive that there is meaning to it after all.

Even within a ‘biased’ frame of reference that hovers above zero, the aliasing principle still holds, with only a minor twist. Concepts that are below a person's minimum level will be projected into some incorrect higher level. Inside this frame, what is perceived as zero or the lowest possible level in whatever aspect, will actually not be zero. It will be impossible to reliably compare any two things that do not happen to fall within the range of the frame of reference, because there is no correct reference point. [TODO: ADD SOME PICTURES TO ILLUSTRATE]

The consequence of this is that it is perfectly possible and in my opinion extremely common, to have ideas that could be considered ‘floating’. The ideas seem to make sense within their frame of reference, but they have no basis that allows to either compare them to other ideas in any meaningful way or determine whether they make any sense from a global point-of-view. Comparing the ideas is like trying to prove that one person is taller than another by comparing the vertical position of the top of their heads—with either or both of them beheaded. Even if only person B would be decapitated, his disembodied head alone cannot be used to determine whether he was taller than A or not. It can be held at any altitude to ‘prove’ whatever desired point.

Cargo Cults

One of the most striking practical examples of trains of thought that have become entirely floating are so-called cargo cults. Certain indigenous cultures that were exposed to Western culture especially during World War II, witnessed events like military air drops and cargo deliveries. These people were used to obtaining goods only through hard work, and could not grasp how wealth could be produced in such quantities. They did not know about factories and workers, they only observed the end result: boxes filled with goods pouring out of flying machines. They mapped their observations onto their own frame-of-reference and considered them magical and the acts of gods. When the war was over and the armies abandoned the bases, the tribes kept alive many of the practices they had witnessed: they built mock airstrips and mock aeroplanes, and created rituals that mimicked military drills and air traffic control schemes. They hoped that by doing this, they would be able to summon the same cargo deliveries they had previously witnessed. The acts of building airstrips and executing military drills had become entirely detached from their roots, but still those people performed them because within their frame of reference, there was a connection between those acts and the goal of obtaining goods.

This is an extreme example. Although cargo cults may be in the process of fading away, their legacy still lives on. In software development, the term ‘cargo cult programming’ describes the practice of always including certain dependencies or copy-pasting source code without knowing what it really does, in the hopes that it shall automagically make the program work.

There is many a more subtle way in which certain thought patterns can become detached from their origins yet kept alive through incorrect mental constructs, and it is not always as obvious as in this example of cargo cults. I am certain the capacity of the human mind to grasp concepts is limited, and people will forget essential core concepts if they keep on learning things at ever increasing levels. At some point they will start juggling with those high-level concepts without realising that they are violating boundary conditions imposed by one of the tiny low-level details they forgot. Maybe you believe you are not subject to this phenomenon, but how could you be so certain of that? While reading the rest of this text, you may notice that a whole lot, if not pretty much all of it, is an attempt to expose many of those floating ideas in present-day human reasoning. My hope is that mankind will learn to anchor those ideas back to the ground before they crash spontaneously, dragging along many people in the process.

A common scenario that spawns floating reasoning is when a single person, or only a very tiny group of persons, solves some very complicated problem. Even if the general public is being explained how the problem was fixed down to all the tiny details, they tend to very quickly forget not only all those details, but also in general how difficult it was to fix the problem. It quickly becomes treated as trivial and for granted. For instance, a large part of the population drives and flies around in very complicated solutions for the problem of transportation. Yet the number of persons who would be able to build a functional car, let alone a usable and safe aeroplane from scratch, is probably quite small, I do not even dare to make a guess at a percentage. The general public only observes the final step required to solve the problem, and therefore never learns anything about the problem-solving process that would help to fix similar problems. That process is simply perceived as magic.

Floating reasoning often reveals itself through excessive use of expensive high-level words, jargon, and acronyms, while lacking the ability to reformulate what is being said into simpler wordings. Needless to say, politicians are quite prone to this kind of behaviour, but it is also common for typical professions that shield their practitioners from the ‘common plebs’ through a barrier of jargon. The persons throwing around all that bloated vocabulary have some vague, often emotional association for each of those words, and glue them together in a way that seems to make sense within the narrow frame-of-reference of those associations. They do not realise and generally do not care that those high-level concepts are built upon a pyramid of important low-level concepts. If there are fundamental holes in the base of that pyramid that compromise its structure, then there is no point in trying to reason with the high-level concepts only. That would not be any different from trying to cast some magic spells in the hopes of making things better, or acting like a cargo cult. One of my goals for this very text is to write as much as possible from the ground up. Ideally, if the reader doesn't understand something, it should be sufficiently explained elsewhere in the text. I am aware that this is rather utopian and I am probably failing horribly at it, but at least I try. Knowing about the pitfalls of aliasing is one thing, avoiding them is something entirely different.

The Cave

The phenomenon of what I dubbed ‘perceptual aliasing’ has been known for ages. Only recently after writing all this, I discovered the following quote by Thomas Sowell that perfectly nails it: it takes considerable knowledge just to realize the extent of your own ignorance.

It goes way further back in history however, as evidenced by the Greek philosopher Plato's allegory of the cave. In short, it tells a hypothetical story of people who have since birth been chained inside a cave, lit only from behind by an eternally burning torch that casts their shadows on a wall before them. Abstraction is made of who has set up this experiment and why, how the people are being fed, and other practicalities about being chained in a cave, because that is not the point of the story at all. Assume there is some supervising entity that controls this set-up and ensures the “well-being” of the persons in the cave despite their strange predicament.

Now consider what happens once they grow up and develop consciousness. Because their heads are limited in movement, the shadows on the wall are all they can see. They will eventually identify themselves with their shadows because they notice that only their own shadow reacts consistently with their movements. Those shadows shall be their self-image and their only idea of reality. Some day, one of them is temporarily freed and allowed to view and interact with the outside world. When he goes back into the cave, the people who remained inside cannot understand what he is talking about because their frame of reference is limited to seeing shadows on a wall. They will rather assume that he has gone insane than believe him. The person who got a taste of freedom will most likely go insane if he is again chained inside the cave of course, because now he realises what a messed up situation it is. The others do not mind being chained because they have never known what it means to be free. A more modern version of this story is featured in movies like ‘The Matrix’ (1999), although there the situation is actually reversed and humans are raised in a fake world that seems a lot more appealing than reality. (By the way, if you wonder why the two sequels appear not to make much sense, it is probably because the directors never made it obvious enough that the ‘real world’ from the first movie was also still a simulation.) I already used the word ‘projection’ and you may have heard this term in a context related to psychology. Indeed, the mechanism of projecting one's own situation and expectations onto others, is very strongly related to what I refer to as ‘perceptual aliasing,’ and this will be explained in more detail further on.

The funny thing is, knowing about perceptual aliasing does not make things easier because it works in both directions. If someone explains something that does not seem to make sense, it might be because it is indeed flawed reasoning or because of inability to understand it. There is a saying: if you can't dazzle them with brilliance, baffle them with bullshit.

This is true, one can knock even the most brilliant people off their socks—at least temporarily—by flooding them with stuff that makes no sense. The trick is to make it seem as if it does make sense. (This strategy was satirised in a 1998 South Park episode where an attorney managed to convince a jury by means of a ‘Chewbacca defence’.) The only way to get around this when it happens to you, is studying the explanation in detail and looking for things that may be beyond your level. If you cannot find any, you can analyse the explanation and prove its (in)correctness. Otherwise, you cannot and must not judge the correctness. Perceptual aliasing, especially in combination with arrogance [LINK:ARROGANCE], can make one feel smarter than others because they say and do things that do not seem to make sense to the observer, while in reality it may be the other way round. If you often feel as if you are the only person who knows what something is about, you are either a genius and really are smarter or more intelligent than the rest, or you really know so much less or are so much less intelligent than all the rest that you are under the delusion of being much more capable and suffering from a severe case of Dunning-Kruger. It is pretty obvious which of these two options is the most plausible.

Most importantly, knowing and understanding the concept of perceptual aliasing does not imply no longer being subject to it. I have heard people referring to it and still obviously falling prey to it every few minutes. I myself am also still subject to it, even despite thinking about and writing down all this stuff. Any reader of this text must be aware of that. Anyone who gets a feeling of: this guy sounds like he knows much more than me, I should blindly believe everything he writes,

should re-think that for a while and be a little bit more critical.

Evolution has provided humans with some hardcoded mechanisms that exploit aliasing from a low to a high level. The most obvious one is probably arrogance [LINK:ARROGANCE]. Even if someone is completely inept, being arrogant enough may create a temporary impression of being actually suitable for a certain task. It is very important to stress that this impression not only manifests itself in the eyes of outside observers. It also—and especially—applies to the arrogant person itself: they will actually believe to be up to the task and not realise that this belief is based on nothing but an assumption. This is one of the causes of the Dunning-Kruger effect. I will elaborate on this further on in this text [LINK:HUBRIS], in this chapter I mostly focus on what happens with regard to outside observers.

The aliasing concept also indicates how dangerous it can be to use ironical remarks in the sense of saying the inverse of what one really means. It is OK to do this with interlocutors of whom it is known they will have the right context to detect the irony. When doing this with unknown people however there is a high risk that they shall interpret it completely differently, perhaps even in a way that was not even anticipated by the person who uttered the ironical remark. But wait, it gets worse. If it was assumed that the other party understands the irony, any reaction (within certain limits) will be interpreted as a confirmation of this understanding. Even if the reaction seems to hint at misunderstanding, it may be perfectly explained as another ironical reply to the original irony. This can spiral out of control quickly, therefore anyone who wants to be certain to be understood and does not want to clean up the mess of such convoluted conversations afterwards, should be smart enough to stay clear of irony and sarcasm. Even though there may occasionally be something like “a lie for someone's own good,” just sticking to the truth will always work best in the long run. If you ever wondered why many languages and cultures have proverbs in the vein of: honesty is the best policy,

and none like: lying and sarcasm work awesomely great,

this may be one of the reasons. Apparently evolution did not work out so well for the civilisations that adopted the latter proverb as a way of life.

Perception Corruption: Catch Me If You Can

People generally only look at a subset, a sampling of characteristics to judge someone's abilities in a certain field, which again justifies why I like to use the term ‘aliasing’ in this context. Resorting to a limited sampling makes sense because it is obviously too costly to perform a complete evaluation. Yet, the subset may be taken way too small to reach even a reasonable level of confidence. If the person under scrutiny can replicate exactly that small subset of sampled characteristics, they will appear capable even if unable to do anything else outside the subset. Arrogance works in this aspect because in a perfect and honest world, people only boast their purported abilities when they truly have them. Most likely, humans initially lived in such simple world, hence evolved the simple initial positive reaction to boasting that we still experience. Only when this reflex had become standard human behaviour, it became profitable to abuse it, and arrogance was born. The next step would be to develop a reaction against arrogance, but it should be obvious that this whole chain of reactions is becoming increasingly long and increasingly inefficient. One could simply reject any boasting, but this incurs a risk of rejecting true abilities. Only when given enough time to get a better ‘sampling’ of a boasting person, it will become apparent whether it was justified or the purported abilities were either exaggerated or plain non-existent.

Put otherwise, within the frame-of-reference of a naïve person who only recognises bragging as evidence of true abilities, any kind of bragging is believed to be proof of competence. People with a larger FOR that includes knowledge about the concept of arrogance will know that bragging can map to more than just a single thing. Either it is evidence of true abilities, or only of imaginary abilities put forward either out of ignorance of the subject themselves, or out of intent to deceive. How evolution ‘copes’ with this is obvious: the naïve who stick to their simplistic subset of observable properties to fathom the abilities of others, will be disadvantaged to such a degree that eventually they shall disappear. Others may develop mechanisms to detect arrogant behaviour. In the best case, maybe someday people will evolve to quicker realise that appearances can be deceiving.

This could be generalised towards a concept of ‘perception corruption’ that is a risk to every entity that observes certain limited parameters to measure the underlying quality of a subject. The estimate of the quality can be corrupted by manipulating either the observable property itself, or at a deeper level, the mechanisms that convert the observation into a true quality estimate. For the entity that is being fooled, there is almost never any advantage in this, unless it becomes aware of the corruption and can somehow exploit the ‘parasite’ in its turn. For the corrupting individual themselves, the initial positive pay-off is likely to turn very negative as well in the long term.

Applied to people, a person could pretend to have certain skills or qualities by mimicking traits that are generally considered evidence for possessing those skills or qualities. All it takes is to figure out exactly what features are being used as criteria, and mimic those features. An excellent example is the true story of Frank William Abagnale, Jr., illustrated in the book and 2002 film titled ‘Catch Me If You Can’. Abagnale had been able to keep up the appearances of being a pilot, doctor, legal prosecutor, and other professions, while in reality being nothing but a brilliant con artist. The film nicely illustrates how he pulled this off merely by mimicking typical superficial traits of those professions.

A simple present-day example: electronic devices with batteries often have two ways to give the user an idea of how long the battery will last. First, the total capacity is printed as a milliampere-hour (mAh) value on the battery itself. It is trivial to corrupt this: just print a larger value (fortunately, the relation between this value and battery life is not obvious and the average consumer barely cares about it). Second, the device will have some active indicator of how much capacity the battery has left. This can also be corrupted by manipulating the algorithm that converts the observable battery parameters (voltage, current) into a percentage or remaining time. For instance, a rudimentary indicator for a Li-Ion battery inside a low-power device that operates at a constant temperature, could use the quite predictable relation between voltage and charge level. This indicator would rely on a lookup-table of voltage versus charge level. It is easy to manipulate this table such that the battery seems to drain slower than it really does. When the battery is really almost empty, the charge indicator suddenly plummets, leaving the owner of the device utterly confused. Obviously, once this kind of fraud is exposed with the general public, the reputation of the manufacturer risks being damaged, annihilating any tiny profit they might initially have obtained by exaggerating their battery capacities. Does this kind of stuff happen in reality? You bet. I have bought a few cheap (and not so cheap) Chinese gadgets and I have found occurrences of both exaggerated ratings printed on batteries, and a misconfigured battery level indicator.

A more complex example is counterfeit money: anyone who can make a piece of paper that looks exactly like a real bank note, has corrupted the monetary system. A bank note on itself has nearly no value, the value lies only in the convention that it represents a certain amount of debt (see also [LINK:WHATISMONEY]). The note can in theory be traced back to the moment where people agreed that it was a valid representation of true debt. A fake bank note however not only has no value on itself, neither does it represent any agreed upon true value. When tracing back its transaction history, it will prove to have originated out of nothing and any chain of debt that was constructed trough the use of the note cannot be resolved. The fake bank note is a false observation of an assumed underlying value. If the monetary system would be swamped with counterfeit money (which can exist under many more forms than just fake bank notes), the system will eventually collapse and everyone loses, including the counterfeiter who will be unable to buy anything with their counterfeit money and worse, not even with real money.

A nice example in nature are breeding parasites like the common cuckoo, that lay their eggs in the nests of other birds. The parasite chick has a reflex to throw the other eggs or chicks out of the nest. It exploits the parental instinct of the abused parent bird, which originally only looked at egg-shaped objects. As a natural defence, some birds have learnt to recognise the ‘alien’ eggs and remove them. In their turn, some breeding parasite bird species have then evolved to produce eggs that look very similar to those of the species they abuse [TODO: FIND ARTICLE]. Again, if this process would continue to the extreme, the bird species that is being abused would become extinct because its offspring is systematically being replaced by the parasite. With this species gone however, the parasite that has specialised itself to profit from that specific species will also have lost its means of procreation because it relied entirely on the extinct species and will disappear together with it. This makes this kind of process long-term stable only when used in moderation on a population that is large enough for the abuse to remain either undetectable or too expensive to combat—one could say, on a population that has outgrown its optimal size and that has become so large that it is more efficient for it to ignore decay than to fight it.

Few will like to acknowledge that many things that have become acceptable behaviour in modern cultures, are nothing more than a similar parasitic corruption of mechanisms that might be crucial for long-term survival in periods of crisis. In the end if any individuals emerge from this, they must be the ones who can recognise parasitic processes in general, and exterminate them in a more deep-rooted manner than simply trying to continue the kind of futile arms race that is only a slow spiral towards probable death. In a certain sense the concept of advertising is an example of perception corruption in human society, at least the kind of advertising that aims to make people buy stuff they do not need. I believe this will eventually disappear through straightforward evolution, and only truly informative advertising shall survive. Every kind of abusive advertising effectively destroys itself in the long term.

Animal Farm

No matter how good their intentions are, teachers at schools often fail because they try to teach concepts at a level way above the pupils' current level. What the students actually learn then—if anything at all—is often not what was intended. The right way to teach something complex or something that requires a certain background, is to estimate the level of the pupils, making sure they have the right frame of reference, and then teach something that is only slightly above that level. Once that has been mastered, complexity can again be increased incrementally. There is no point in starting at a level way beyond what the students can handle. They will either learn nothing at all or something completely wrong. They may end up with a hatred towards the subject because it does not seem to make any sense, to such a degree that they may not even want to learn about it when they have grown up and reached the correct level.

This is also why I believe it is ridiculous and counter-productive to force pupils in high-school to read entire literary works in the likes of ‘1984’ or ‘Animal Farm,’ or to try to force them to appreciate other ‘adult’ works of art like classical pieces of music or paintings, by totally dissecting those down to the tiniest details of the specific interpretation of some jumped-up critic. Although there may be some pupils who will at that age be able to understand what those works actually are about, I believe most of them will not learn anything useful. They will study everything by heart the teacher expects them to know about the works and regurgitate it at the exam. All that remains in their memories afterwards will be the sour aftertaste of having to read through a seemingly boring book that was full of incomprehensible gibberish and memorising spoon-fed conclusions just to pass the exam.

I am not saying those books should be completely dropped from the curriculum, on the contrary. They should still be discussed, but only through fragments and general summaries, maybe a movie adaptation, not by force-feeding the students with the complete unabridged works. It should be an introduction that could lead to the students eventually reading the books by themselves should they want to, be it immediately or many years later.

I can remember as a teenager having read a book in Dutch from the early twentieth century that might have had pretty much the same goal as this very text. I cannot remember which book it was and what its message was exactly, because I did not understand it. It tried to go from a low to a high level by starting out as a children's fantasy story but it obviously failed: after a few chapters I lost track because it took a huge leap and the rest of the book was above my level. If you are way past high-school by the time you are reading this, try picking up one of those books again or watching those old ‘uncool’ movies they forced you to watch. You might be surprised at how much you missed back then. If you are still in high-school, just try to learn the minimum you need to pass the exam and set a reminder in your agenda to revisit the work in ten to fifteen years when you have more cultural baggage to truly appreciate it. Do not point your teacher towards this text. If you plan to do it anyway, don't tell me I did not warn you, and first ask yourself whether you truly understood the whole point of this entire chapter.

The Box

If this all sounds new to you, keep in mind that it probably is not. You probably have heard the phrase: you should think outside of the box.

It is the same thing. The box represents the frame of reference. The saying means one should try to break out of their current frame of reference and think in a way they never did before. This is possible but very hard, and most will not do it spontaneously, only when forced to (which may be when it is already too late). And the ‘distance’ one can leap outside their current ‘box’ at one time is limited. Most people probably believe they can think outside their box but are actually only looking at things from another corner within the same box. [could link to XKCD 915].

The problem is, I am certain the size of this ‘box’ is inherently limited. It depends on the computational abilities of whatever entity is trying to model its surroundings. Considering humans, those computational abilities vary wildly between individuals, but there is a strict upper limit. When trying to model a topic at a very high level, for instance some specific specialisation in biology, the only feasible way is to make the box ‘float’, centred around that high level, such as to be able to grasp all the tiny details of the topic. This means the person will need to reduce its modelling accuracy of everything outside that specialised field, possibly to the degree that nothing else is modelled at all. Such persons would become professional idiots. My definition of an idiot is tightly tied to my idea of perceptual aliasing: I consider an idiot “a person who has strong ideas that are based on only a narrow frame-of-reference, and who will not deviate from these ideas even in the presence of obvious evidence that proves the ideas incomplete or incorrect.” (This definition is different from the average person's by the way, which I believe to be rather something like: “a person who has different ideas than mine” [LINK:EVERYONEISLIKEME].)

The only way to model a wider span of topics is to reduce the amount of detail per topic. In other words, it is futile to try to know everything. Those who try it anyway, tend to over-specialise only in a narrow field such that they can keep up the illusion of being omniscient, because they always know more from that narrow field than pretty much everyone else. They simply ignore every indication that they know almost nothing outside those few fields, because that would put a dent in their egos [LINK:ARROGANCE]. The only tractable strategy not to become either insane or an idiot, is to try to keep an overview at all times and temporarily drill down on details when necessary. The sheer complexity of the present-day world, combined with increasingly unreasonable expectations, makes this increasingly difficult. This may be one of the reasons why we have a culture that produces an ever larger number of professional idiots who cause an ever larger number of problems whenever they need to interact with anything outside their ivory towers. Moreover, these professional idiots also become increasingly grumpy because the abundance of communication systems makes it increasingly difficult to keep up the illusion of the the ivory tower.

The core idea of what I am trying to explain with this entire text is very susceptible to perceptual aliasing. It is pretty much a binary thing: you either get it or you do not, and the opportunities for aliasing are huge, in all directions. The idea itself is very simple but to truly understand it, one needs an enormous amount of knowledge from various domains. It is very possible that some parts of this text are a load of hogwash because I am making mistakes that are too high above my level for me to detect. Some will probably think the entirety of this text is hogwash because they are unable to understand it. Do not feel too comfortable if you think you can understand or rebuke everything, because it could be an illusion. Do not blindly believe either what you read here and anywhere else, verify it if you can. It is not because something is written in print or in an official-looking and tidy lay-out with a big name on it, that it is true. And realise that next to ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, there is always the possibility of: “I don't know.” In many cases, that is the most useful judgement one can make about something. If you cannot verify something, always keep remembering that you have not verified it, until you can. Do not pick a random or convenient decision and consider it true.

The most obvious problem with aliasing is that even those who are aware of it are still subject to it. It takes a considerable change in mentality to reduce the risk of stepping into one of the many aliasing pitfalls. The risk can never be entirely eliminated because that would require infinite knowledge. The solution is to become aware of the inevitable limitations and to learn to model uncertainty instead of always trying to map everything to something known.

The Bad Touch

Coming back to The True Meaning of Life™ I kicked off this entire lengthy rant with: it is present in many locations outside this text, some expected and some unexpected. People are exposed countless times to all these ‘hints’ without recognising them, due to lack of the right frame of reference. Remember the song ‘The bad touch’ by ‘The Bloodhound Gang’? Yes, it is silly and few will ever consider paying any attention to the seemingly inane lyrics, given TBG's reputation. Yet, the refrain: You & me baby ain't nothing but mammals, so let's do it like they do on the Discovery channel

summarises the longer ‘meaning of life’ explanation I have given above. A less obvious example is ‘Imagine’ by John Lennon. Unlike TBG, Lennon probably better understood how pointless and potentially dangerous it is to throw such a difficult message into people's faces, so he wrapped it in a formulation that seems harmless to anyone who is not ready for it. (Eventually though, perhaps the formulation proved not harmless enough for him to not get killed.) There are countless other examples, in books, movies, art. The best examples are often the ones that are the least noticed. For instance, it was only when I watched ‘Ghost in the Shell’ (1995) for the second time, that I noticed how much overlap it has with topics I had touched upon in this text before even seeing the film for the first time. It is not an easy film to grasp, which explains why I was overwhelmed during the first viewing. Luckily it is so visually stunning that it lured me into a second viewing, which gave me more than I bargained for. Keep this in mind if you have never watched it and intend to: it has way more depth than the common contemporary Hollywood production, and it does not spell out things for you. But once you can get through that depth, the reward shall be great.

I somehow learnt enough stuff over the duration of my life to come to the conclusion I started this text with, and be fairly confident about it. Theoretically, I could start from a reasonable level of knowledge that most readers should have attained and then try to gradually build upon that, to finally explain why I believe my explanation is likely correct. However, that is pretty much impossible. It is hard to guess what this ‘reasonable level’ should be, and if I would estimate it conservatively low I would have way too much to explain and the text would be full of redundant fluff for many readers. Therefore I will only explain some important key concepts and I will leave it up to the reader to learn more if they think they're missing something. You are reading this text from the Internet, which means you should have access to pretty much all the knowledge required, if you can manage to dig it up amidst the gigantic amounts of garbage amongst which it is hidden. Even if you are somehow reading this after humanity has completely fucked up and you have to dig up books from the ruins of a library or school, then by all means do it.

Occam's Razor

You might be wondering how I can be so confident that “zero” is the most likely outcome of “the equation of life.” Some might accuse me of picking a degenerate solution (in the same sense that zero is always a solution for x in A⋅x = B⋅x2), but I don't think so. There was this monk at the turn of the fourteenth century who came up with a great idea. His name was Occam, or Ockham or however you like to spell it. If there is anything you should learn from what I am trying to tell here, it is that it does not matter much who thought up an idea, when they lived and how their name is spelled, it is the idea itself that counts. And the idea at hand boils down to this: the simplest explanation that fully explains a phenomenon is also the most likely to be the correct explanation. Or likewise, the simplest effective solution to a problem is also the most likely to be the truly correct solution. You may be inclined not to trust something thought up by a medieval monk but it makes perfect sense. There may be multiple definitions of ‘simple’ in this formulation. A popular one is: “having as few assumptions as possible,” but in practice pretty much any interpretation of ‘simple’ shall do.

Rote Learning

A typical way in which people try to explain a phenomenon is to just record the conditions of the phenomenon and its outcome and store this as a fact that can be played back later. If A, then B.

And if that proves not to be accurate enough: if A and B, then C.

Facts keep on being piled up and add to the rule. At a certain point the rule may become something like: if A and B but not D when A is E and B is F and if C is somewhat like G and B seems to be a bit like H, then C.

And anything that does not fit within this model is an exception and should be ignored, because it is just too much hassle to further extend the model. The fact that the model might be rubbish is not to be questioned because hey, it took a damn lot of effort to make it.