Another Reason Not to Buy DRM-Protected iTunes Songs

This page is now mostly historical, but you may still want to read it if you bought a lot of iTunes tracks before 2009 and have not yet replaced them.

When the iTunes Music Store (abbreviated to iTMS in the rest of this text) first opened, it only contained music in 128kbps AAC format, with an added copy-protection layer called FairPlay. FairPlay is a kind of DRM, which officially is an abbreviation for “Digital Rights Management,” but which I always read as “Digital Restrictions Management.” There's no way around it: not a single comsumer wants DRM, only the RIAA does. It has to be said, the DRM featured in iTunes is one of the less obnoxious ones. It still allows to play songs on 5 computers at the same time, and one can burn the songs to an audio CD. The latter is a loophole that allows to create a DRM-free copy of the song, by ripping it again from the CD-R(W). However, this is not such a good idea as I'll explain below. Luckily, Apple has introduced “iTunes Plus” songs, which are not only DRM-free but also of higher quality. Since the middle of 2009 all old DRM-infested tracks have been removed from the iTunes Music Store, and most have been replaced with iTunes Plus versions.

The main reason to avoid the DRM'ed iTMS songs (or DRM'ed music in general) is of course the DRM itself. They can only be played in iTunes or on iPods, unless the tedious loophole described above is used. However, there is another reason and it's a rather disturbing quality issue. First of all, the songs are encoded at a measily 128kbps. Even though they are in AAC format which is a bit more efficient than the ageing MP3, 128kbps still is not enough to come even near CD quality. Not even in the most performant codecs like Ogg Vorbis, which can offer good reproduction starting from 180kbps. If you use the ‘CD-R loophole’ and re-encode the ripped song to MP3, you'll lose even more quality. But that's not the end of the story…

In order to maintain acceptable audio quality within the limited 128kbps bitrate, Apple has applied a lowpass filter to all the DRM-protected songs before encoding them. Mind that this isn't bad as such. It's is a pretty normal and desirable practice: if one encodes MP3s with the high-quality LAME encoder on standard settings, it will also apply a lowpass filter when encoding to a low bitrate. The reason is that it's better to drop the (less important) highest frequencies so that the low frequencies can be encoded more faithfully, than trying to encode everything and introducing audible artefacts everywhere.

However, the lowpass filter used on the iTMS songs is pretty harsh: it's a ‘brickwall filter’ that cuts off everything at 15.5kHz! Some interesting figures: humans with undamaged ears can hear up to 18kHz or even 20kHz. This is why CD audio goes up to 20kHz. FM radio is lowpass filtered at 16kHz. In other words, standard iTMS songs have worse sound quality than FM radio. Even if your ears only work up to 16kHz (which is inevitable as you're getting older), the presence of the brickwall filter will still mess up the highest frequencies, because the steeper a filter is, the more it messes up the phase of the frequencies near the cut-off point. This translates to distortion of stereo effects and noise-based sounds like cymbals and hihats. If your ears are actually able to hear up to 18kHz or more, 128kbps iTMS songs will sound less ‘crispy’, or more ‘dull’ on good equipment than their original versions.

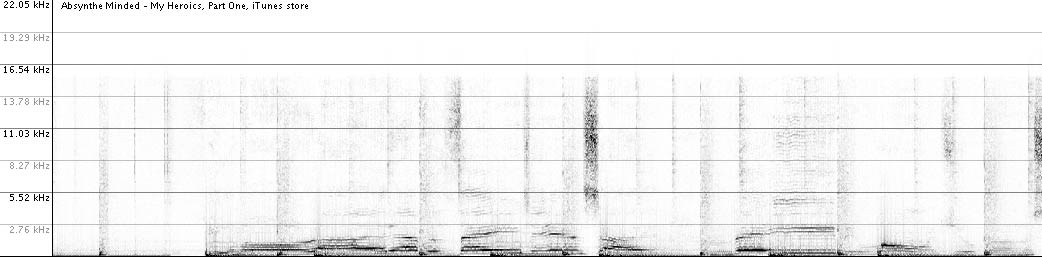

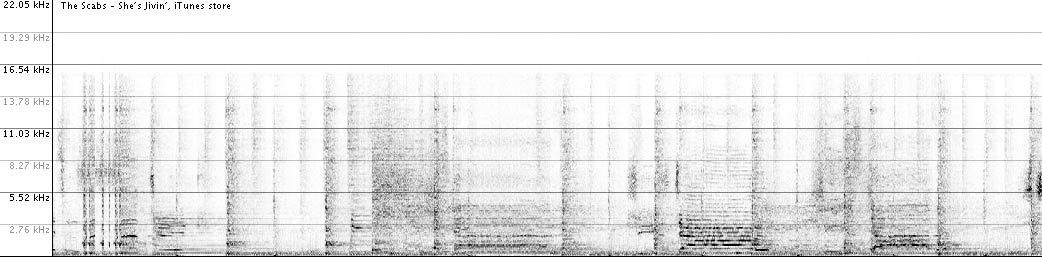

The reason why I noticed this brickwall filter, is that I like to look at the frequency content of songs. I wrote the SpectroGraph iTunes plug-in specifically for this. Here's a spectrogram of the first DRM-protected song I ever bought on iTunes:

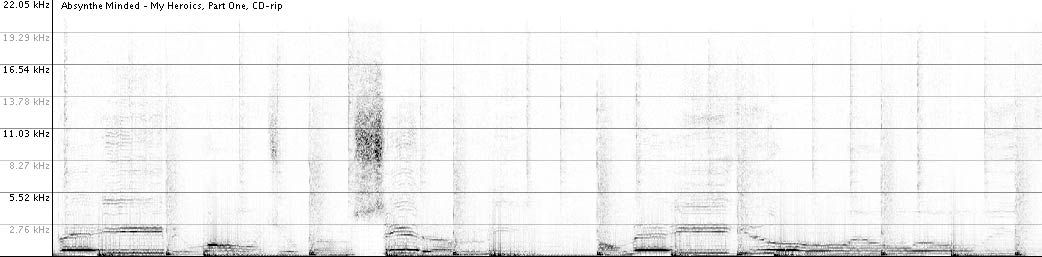

A few weeks later, I discovered I had the same song on a compilation CD, so I ripped it. This is a spectrogram from the CD-rip:

It are not exactly the same parts, moreover SpectroGraph didn't always run at the same speed, that's why the time scale is different. However, you can see that this spectrogram goes all the way up to 20kHz, while in the iTMS one, all frequencies starting from about 15.5kHz are obliterated by the brickwall filter.

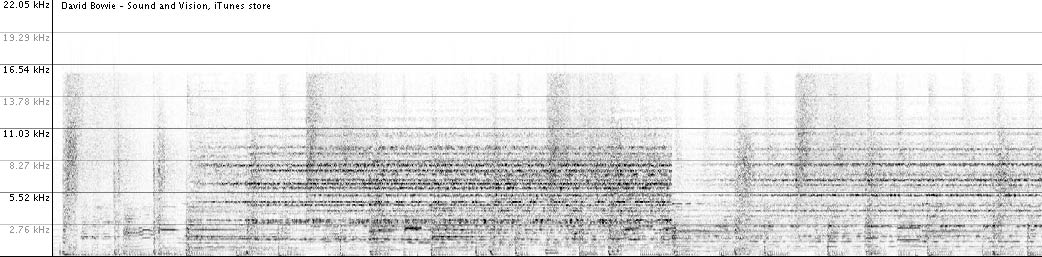

Because this may not be so convincing, I wasted a Euro on buying another song I already had. I didn't only choose this one because of its nice applicable title, but mostly because of the high-frequency content of that “sizzling steak” cymbal. This is the iTMS spectrogram:

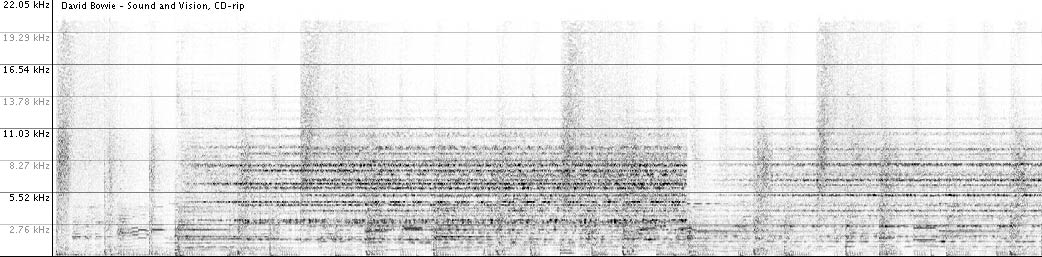

As you can see, exactly the same brickwall filtered characteristic. Here's my own rip from exactly the same CD (The Singles Collection). This time I managed to match up the parts pretty well:

To top it off, another spectrogram from a DRM-protected iTunes store song. I don't have a CD version of this, but the appearance of again the same brickwall at 15.5kHz speaks for itself.

How about iTunes Plus songs? Well, as expected they aren't lowpass filtered, because 256kbps AAC is capable of encoding the whole frequency range quite faithfully. Since Apple lowered the price of (most) iTunes Plus songs to the same level as the DRM'ed songs, they dropped the DRM version altogether when an album is available in Plus. So you can't accidentally punish yourself by buying the wrong version. With most or even all of the major labels providing DRM-free music in the Amazon music store, Apple couldn't stay behind and started upgrading its entire catalog to ‘iTunes Plus’ at the start of 2009. True, iTunes Plus tracks are still in AAC format, which isn't supported by many MP3 players. But that is the fault of the manufacturers of those players. AAC is as open and subjected to licenses as MP3, and it is higher quality, so I wonder why so many devices support a crufty closed and license-heavy format like WMA, but not AAC. What I really would like to see, is all stores and all MP3 players offering support for the license-free Ogg Vorbis format, whose performance rivals even the best licensed codecs. But that is not going to happen anytime soon, especially because Apple Inc. has some kind of allergy to this format. Moreover, the MP3 and AAC patent holders have managed to spread probably unjustified fear for litigation if any major corporation dares to use Vorbis, despite the fact that it has been designed to be free of patented source code.

So to make the story short, if you have bought DRM-protected songs at the iTunes store, you paid a dollar or Euro for a crippled mediocre-quality copy, comparable to a cassette recording of an FM broadcast. I would expect to get better quality for that price. These prices are near the price of an actual CD, but the quality isn't at all. It's no wonder that those Russian music stores where you pay reasonable prices for good quality, and can sometimes even choose your favorite bitrate and format, are so popular. So the upgrade of the entire iTMS to iTunes Plus is not just a gain on the user-friendliness front, but also on the quality front. I advise to upgrade all your favourite old DRM'ed tracks to Plus versions. The ¢30 surcharge is worth it, not only from a quality point-of-view, but also because those tracks will become unusable chunks of binary data if Apple at some point stops supporting their DRM mechanism.